As the job market evolves and the demand for skills less vulnerable to AI (Artificial Intelligence) disruption grows, higher education must adapt. Monash University’s Advanced Simulation program offers an exciting new approach, emphasizing interpersonal skills and preparing graduates to thrive in the rapidly changing workforce.

Introducing Advanced Simulation: Leveraging Interpersonal Skills for the Future Workforce

Dr. Joel Moore, Director of Postgraduate Education in the Faculty of Arts at Monash University, designed a five-week intensive post-graduate program known as the Advanced Simulation. Joel and Nashid (the second author) have been teaching this program for a few iterations now. This innovative program enhances high-level professional skills by requiring students to apply their disciplinary expertise in a high-pressure collaborative environment. Students must demonstrate a variety of in-demand interpersonal skills less vulnerable to AI disruption:

Applying prior disciplinary knowledge: Students use their expertise to address complex issues in realistic, shifting scenarios, honing skills that are difficult for AI to replicate.

Critical analysis and collaboration: Students work together to analyse goals and motivations of various actors, demonstrating teamwork and interpersonal skills that remain essential in the evolving job market.

Communication across disciplines: The program trains students to effectively communicate with and work alongside non-experts on interprofessional teams, emphasizing the value of empathy and understanding in professional settings.

Adaptability and Implementation: Preparing Graduates for an AI-Driven World

Postgraduate training should prepare graduates to thrive in complex, ambiguous environments. The versatile Advanced Simulation program achieves this by requiring teams of students to both compete and collaborate in the pursuit of organisational goals within the context of simulation scenarios centred on global challenges. The diverse teams work hard to harness their collective expertise, achieve their goals, and work towards practical solutions.

For example, when a team representing an international labour NGO sought to overcome the poor working and health outcomes for foreign workers on Malaysian palm oil plantations (a core part of the simulation scenario), they identified a language and interpretation breakdown as a key contributing factor. The team, composed of Applied Linguistics, Interpreting and Translation, Media and Communications, and Public Policy programs combined their collective expertise to craft a detailed training program for plantation supervisors. They prepared a high-impact pitch and convinced the teams representing plantation executives to implement their program.

By emphasizing interpersonal skills and collaboration in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity, the Advanced Simulation program offers a highly effective approach to higher education that equips graduates to succeed in the rapidly evolving workforce in the age of AI.

Applying Prior Disciplinary Knowledge

Groups of students are formed into interdisciplinary teams and must pursue collective goals by creatively applying their expertise and skills in concert, negotiating with, and persuading multiple stakeholders in complex, fluid scenarios.

In the simulated professional environment, as in actual professional environments, teams must use effective communication, persuasion, and negotiation to leverage the diverse capacities of their members and influence stakeholders. The time pressure and realism of the simulated environment creates an opportunity for students to develop and demonstrate these capacities at quite a high level.

For instance, in the international NGO team, members applied highly specialised expertise, not as an isolated academic exercise, but building on the insights of their peers –creating new knowledges and approaches targeted at solving real world challenges. Without the knowledge about the challenges of language training, the ethics of interpretation, the realities of the motivations of plantation owners, and the regulatory environments involved, the solutions the team came up with would have been impossible. Only by applying individual areas of expertise in complementary ways, by being more than the sum of its parts, could the team achieve what it did.

Critical Analysis and Collaboration

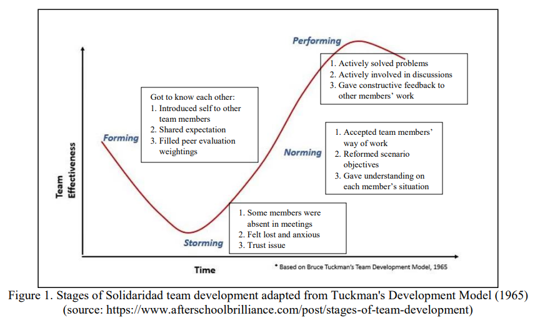

Communication across disciplines and collaboration involved the interdisciplinary post-grads in the same team critically analysing the objectives and enterprises of diverse stakeholders while actively participating in teamwork and interpersonal skills. The team spokesperson reflected that their group could effectively collaborate, work in a team, and use each other’s insights by following Tuckman's group development dynamics.

The team solved the problem through inter- and intra- group discussions and constructive feedback. The team spokesperson, a communication specialist, made a mind map of the findings from the team-members and suggested an objective, which was later revised and approved by the team. To achieve the team objective in the fourth week of the simulation, the team followed the timeline of the action plan set out by the team members. All of them also agreed on the scenario objective.

To succeed, the team members adhered to their action plan through the fourth week of the simulation, which included liaising with other internal teams and critically interpreting external organisational goals, objectives and demands, followed by negotiations with them.

Communicating with Non-experts Across Multidisciplinary Teams

Advanced Simulation provided an opportunity for professional communication with non-experts in an interprofessional team, recognizing, understanding, and practising the value of intellectual exchange and empathy towards non-experts in the inter-professional setting. Emily (pseudonym), as a communication specialist of the same group, simulated her team's community-related tasks, arranging meetings with other groups and acting as the group's spokesperson.

Emily’s contributions were intensively delivered starting in the third week of simulation, the media engagement week when all groups were encouraged to leverage the social media channel to achieve the scenario objectives as part of strategy execution. While finalising the communication strategy proposal, she prepared a media engagement plan for her group and got it approved by the team.

But as a part of group collaboration, Emily was able to handle issues relating to a joint press release between her organisation and another team representing a powerful international environmental NGO -most of whose members were non-experts in media communication.

When she wrote her teams’ press releases about the Sustainable Palm Oil Project, she also faced challenges explaining the deals to external group members because they did not have communication backgrounds, and those who did had never had experience writing a press release. To address the issue, when the RSPO team, for example, asked Emily how to share a quote, she explained what it looked like in the press release by giving some examples and sharing expected content. Because of these difficulties, the press release writing and approval took Emily extra time to complete, requiring the teams to adjust their timelines and reflect on how to address the challenges more effectively in the future.

This implies that communication and negotiation with non-experts across the multi-disciplinary team is an integral part of the simulation unit that enables the post-graduates in honing real-life professional skills and in practising intellectuality and empathy towards non-experts in inter- and intra- professional contexts.

Against this background, the Advance Simulation experience resembles real-life knowledge acquisition and assists post-graduate students to acquire professional skills less vulnerable to AI disruption. Due to the ambiguous and open-ended nature of the course, it is described as one of the most effective means of adapting to constantly shifting professional settings by practising critical and evaluative thinking, tailoring skills and knowledge through dynamic interactions.

With this experiential learning in a time-critical manner, students will not only learn complex professional skills by knowing, doing, and relating, but will constitute their fluid professional identity by engaging in professional development in the current ever changing globalised work contexts.

Pragmatically, Advanced Simulation unit prepares the (post)-graduates with unique professional skills that are less likely to be replaced by AI.

The program can be adapted across disciplines, including its pedagogy and assessments. The main aspect to consider for effective teaching of the subject is how to craft instruction for understanding and learning in an ambiguous learning environment.

Those considering this form of teaching can use follow-up activities to assess students' understanding and use de-briefing and reflections in between simulated activities to enhance critically analytic learning.

Joel is a Senior Lecturer and Director of Postgraduate Education in the Faculty of Arts at Monash University.

Nashid has taught at Monash Arts for five years. She is a PhD candidate at Monash Education, investigating immigrant teachers’ professional identity in Australia. Amongst her study interests are teacher professional identity and theories, career development, academic literacy, curriculum development, and English language teaching and learning in intercultural contexts.