A focus on the alphabetic principle is a faulty guide for literacy instruction.

This standard phrase, used to characterise the English language as a system in which the alphabetic letters function to represent the sounds of words, is a warped and limited view of our language.

With the recent PISA and NAPLAN testing showing a steady decline in Australia’s English and Mathematics results, it is no wonder that people are scrambling for answers. Education Minister Dan Tehan acknowledges that “we’re flat lining as a nation” and troublingly identifies “phonics” as the saving grace as we “strip back” the “crowded” curriculum and focus on “the basics”.

It is not the basics that are missing in Australian education, it is the multifarious aspects of language and linguistics which all teachers must have the confidence to teach, that will improve the literacy outcomes of our upper primary and high school students.

So what are ‘literacy skills’ exactly?

The typical definition of literacy is the ‘ability to read and write’, with no mention of spelling. Spelling is a unique skill; Crystal (2013) acknowledges it as the bridge which interrelates reading and writing, and for this reason, it needs to be given separate acknowledgement as a skill.

Spelling is integral to writing, and people who are not fluent and accurate spellers can struggle to write coherent and accurate texts. When a person is unable to spell a word with automaticity, the higher order thinking processes involved in generating ideas and representing them in written form (Graham & Santangelo, 2014) are disrupted. Students will too often select alternative words for their writing, which they are more confident in spelling, even though they may not convey the intended message with the same degree of accuracy and nuance.

Research has also indicated that when children learn about words and word parts, this knowledge can transfer to reading (Moats, 2005). Good spelling instruction involves teaching students about the meanings of words, which ultimately improves their receptive and expressive vocabulary (Rosenthal & Ehri, 2008), which can be used in the context of written as well as spoken texts.

A National problem

The view that beginning literacy instruction should only address phonological influences on orthography, while avoiding other linguistic influences like morphology and etymology has been labelled by Bowers and Bowers (2018) as the ‘phonology- first’ hypothesis. Learning to unpack the English language must involve the process of learning to abstract, apply and interconnect phonological, orthographic and morphological knowledge from the beginning of learning to write (Bahr 2015; Berninger, 2010). As Venezky (1999) wrote, “English orthography is not a failed phonetic transcription system, invented out of madness of perversity. Instead, it is a more complex system that preserves bits of history (etymology), facilitates understanding and also translates into sound.’

For several decades, a number of researchers have argued that spelling knowledge develops in sequential stages or phases. However, a growing body of research supports the view that learning to spell may not follow a developmental, linear trajectory. To be clear, there is no evidence to support developmental stage theories of learning to spell (Kohnen, Nickels and Castles, 2009). In their attempt to improve literacy results, school leaders often purchase commercial or published programmes to be put in place across a whole school. The problem with this is that commercial programmes not only vary in quality, but the underpinning theory about how spelling is learned is not based on the most up to date research (Davies, 2011).

Why textbooks are not teachers

In line with Education Minister Dan Tehan’s views of a linear, phonics approach to early literacy instruction, commercial phonics programmes have been mandated in many schools. The danger here is that spelling instruction is programme- centred, instead of student- centred, leaving teachers unable to meet the diverse needs of learners in their class- because one size does not fit all.

Evidence suggests that phonics is most effective in the context of a broader literacy curriculum (Camilli, Vargus, & Yurecko, 2003). What is problematic, is that for advocates and teachers of commercialised phonic programmes (which sequence the order of sounds based on student ages), there is no broader context. Grapheme- phoneme correspondences are taught in isolation and without meaning to student learning, or without any reference to quality literature. There is growing consensus that phonics instruction is not working for all children, with little or no evidence that phonics is effective for spelling, vocabulary and reading comprehension (Bowers & Bowers, 2017).

It is thus vital that our teachers are highly skilled in the teaching English orthography as a morphophonemic system, confidently understanding and teaching how spellings have evolved to represent sound (phonemes), meaning (morphemes), and history (etymology) in an orderly way (Bowers & Bowers, 2017). This needs to be done without restriction of a student’s developmental age.

The goal set by politicians therefore needs to shift from one of ‘back-to-basics’, to all students understanding why words are spelled the way they are in order to improve literacy outcomes, measured in terms of reading words, spelling words, developing vocabulary and improving reading comprehension.

The trouble with our NAPLAN decline

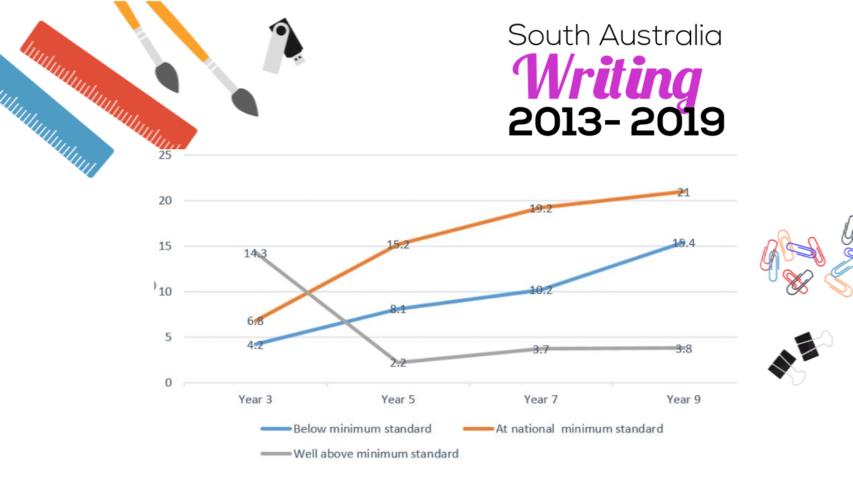

In 2013, our current Year 9 students sat their first NAPLAN test, back when they were in Year 3. We can therefore track their performance over time. Showcasing the writing results is useful because all grades are marked against the same ten assessment criteria, with the minimum benchmark level for each grade changing, much as you would expect given the difference between Year 3 and Year 9 students.

In South Australia this year, only 3.8% of our Year 9 students achieved well above the minimum national standard. This is compared to when they were in Year 3, where 14.3 % of these students were high performers. This data, which is consistent across all literacy areas and all states, shows that our highly able students are the ones suffering.

Not only are we letting down our highly able students, but the number of struggling students only rises. In 2013, only 4.2 % of students were below the national minimum standard, but this year, 15.4% of that cohort were underperforming. We cannot afford to therefore ‘teach to the middle’ or in fact, teach to the bottom. Teachers must find a way to differentiate instruction, but how is that possible when a ‘one size fits all’ sequence of learning is being mandated?

These trends are consistent across all states, and all literacy areas. It has been identified that children who performed well in reading, writing, spelling and grammar in Year 3 stop making the same gains in later years. In an aired interview, Dr Pete Goss identifies that, “it is the transition from primary to secondary school where reading progress really begins to slow down, although we don’t really know why. To reach the national minimum standard for reading in Year 9, students have to read at about a Year 5 level. This year, 20% of NSW students were below this level in reading.”

This is the true national literacy crisis and it won’t be solved by focusing on phonics in the early primary setting.

What would happen if we shifted our focus and taught spelling well in upper primary and high school?

Research shows that while spelling, grammar and punctuation jointly influence written composition in the middle and upper primary school years, spelling appears to be the main predictor (Daffern, Mackenzie and Hemmings, 2017). Furthermore, if difficultly with spelling persists beyond the primary school years, students may avoid writing and develop a mindset that they cannot write, which may then lead to arrested writing development (Graham & Santangelo, 2014). Could current claims of technology being the reason for our literacy decline in high school therefore be seen as a cop-out?

It is clear that current teacher training leaves many teachers with a very weak understanding of the linguistic principles that guide our writing system. Without adequate knowledge about language structure, how can we expect teachers to have the metalanguage needed to help them talk and think about language, or explain it clearly to their students? On top of this, there is a tendency for early career teachers to follow the lead of their more experienced peers in schools, who may be implementing practices that do not necessarily reflect current research evidence (Adoniou, 2013).

It is imperative for school leadership teams to support teacher understanding of the metalanguage needed to unpack vocabulary encountered when reading, to analyse spelling errors within the context of student writing, and to implement a range of instructional activities to meet the specific needs of learners in a classroom.

These sustainable teaching practices are no different for the teaching of five year olds, or fifteen year olds, the language of true linguistics does not change, only the content and vocabulary does.

So what can be done?

Use a linguistic lens

Teachers need to clearly understand English orthography and know how to unpack the underlying structure of words by approaching word study through a linguistic lens. Teachers should explain:

- Phonology as the conventions that govern how graphemes represent phonemes

- Morphology as the system that organises the elements of meaning, identified by base words and affixes

- Etymology as the historical journey of a word through time and its relationship between words both past and present

Analyse student writing samples

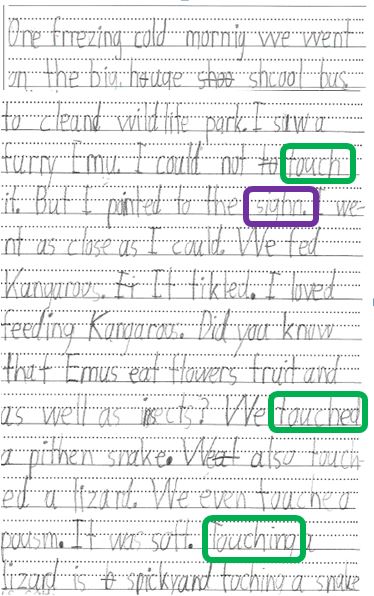

Teachers need to find their teaching points from the context of student writing. This writing sample is from a Reception student in Term 2. This piece of work proves student understanding of the underlying system of how words are constructed in English and analysing these spelling errors is a powerful strategy to draw students’ attention to orthographic structures. This student is correctly writing the base word ‘touch’ and using her morphological knowledge of –ed and –ing as suffix patterns. This student is also correctly writing high frequency words such as <could> and <know>. This is evidence that we cannot have students stuck in a developmental stage defined by a program.

The spelling error <sign> could be highlighted as the specific error to focus on, and as she can correctly record the sounds in this word, she needs another ‘lens’ to examine this word through.

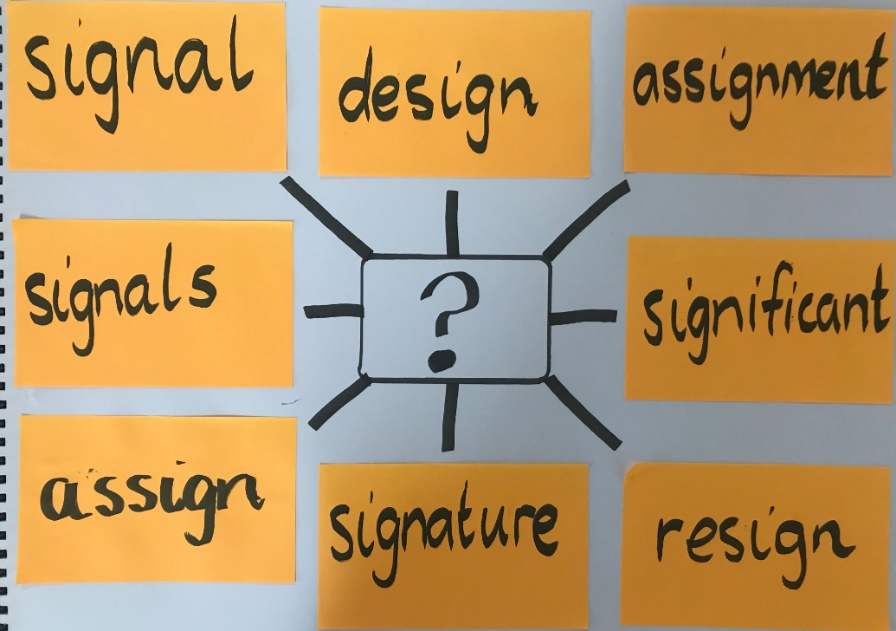

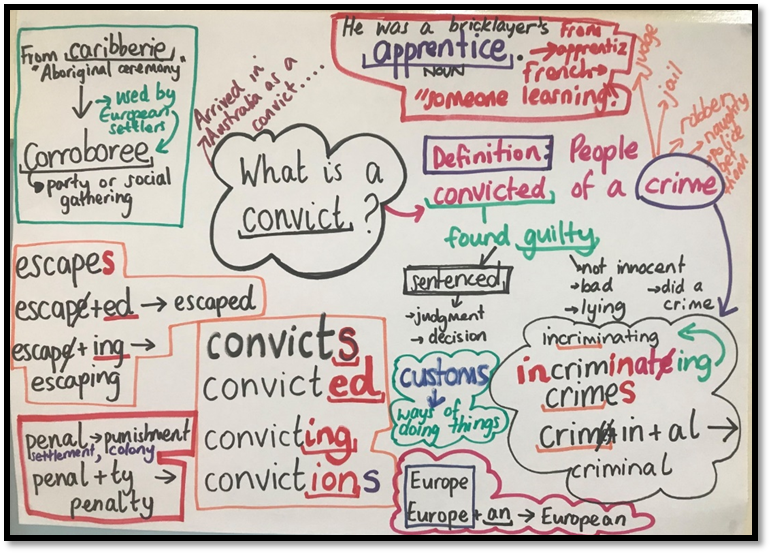

Showing the students a ‘word-web’ of morphologically related words, meaning they belong to the same family in terms of meaning, utilises a morphological lens. Students can identify the shared base, which is <sign>. By exploring the meaning of the word <sign> and connecting this meaning to all of the other words, students can share in a discussion that they must all come from the same root.

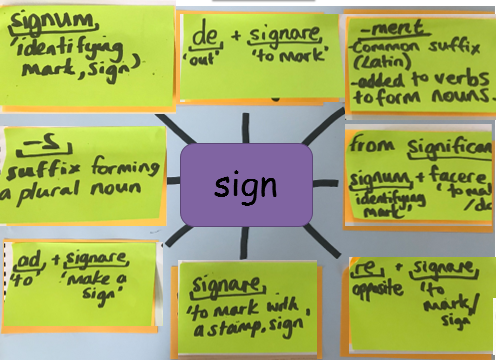

Inviting students to put on an etymological lens, to look at the history of the word to identify connections, allowed the students to understand that the word has an etymological story which impacts the morphological structure and the choices of graphemes. Although we were using our morphological and etymological lens here, it was the perfect opportunity to discuss the difference in pronunciation between the words <sign> and <signal>.

Spoken English uses inconsistent pronunciation of morphemes and this is a perfect example. What connects these words is their morphology.

The consistent spelling of the base <sign> for all words in the family, show us that this English is a highly logical and organised system. These two words are linked in meaning by the base. It is not about irregular spelling or pronunciation. Sounding out is not going to help here, the morphological connection will.

Classroom conversations

Morphemes are easy to work with because they are intrinsically meaningful. Students who can decode single words when reading, but who struggle with reading comprehension have been found to have poor morphological awareness and it is students’ morphological knowledge which predicts success in reading more effectively that phonological knowledge, especially over the long term.

With this in mind, ‘classroom conversations’ are a great resource when unpacking vocabulary in texts. The importance of the teachers being confident to ‘jump in’ and unpack vocabulary using the correct metalanguage is evident here. These lessons cannot be forward planned, and cannot come from a prescribed book. They are based on the conversation which arises from the students, as they unpack a story for the first time and encounter new vocabulary, with explicit guidance and instruction from the teacher.

Using the International Phonetic Alphabet as a tool in the classroom

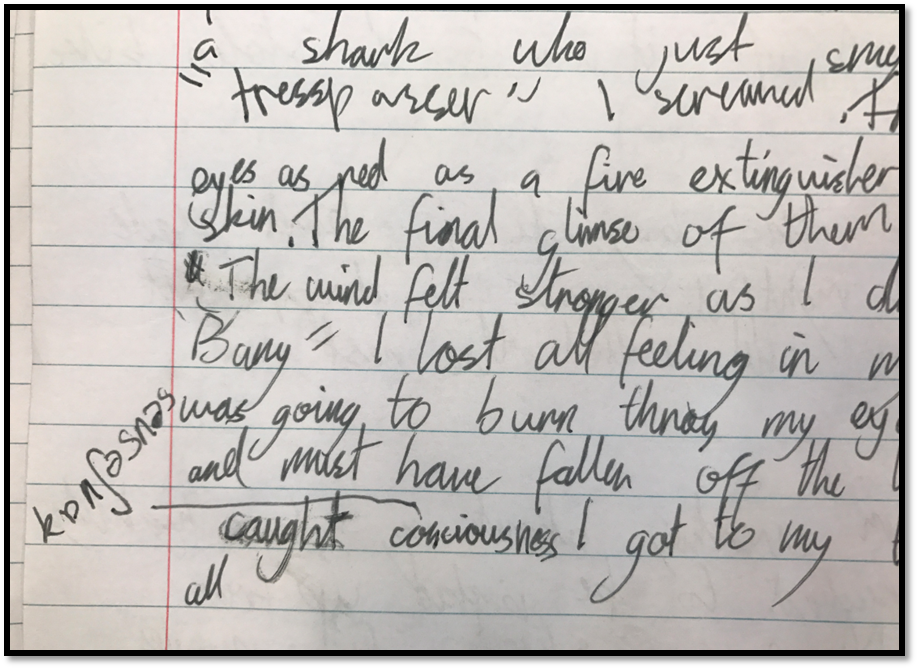

The International Phonetic Alphabet is an incredible tool which develops student agency and self- efficacy. This example below shows a Year 4 student who struggled to write the word <consciousness>. She was able to articulate the sounds, and by writing it in IPA, could identify which grapheme was difficult. Giving students the tools to self- analyse their own spelling errors and edit their work independently, sets them up for success in the long run.

A recent survey of Australian preservice teachers indicated that they had significant gaps in their knowledge about language structures such as syllables, morphemes, phonemes and so on (Meeks & Kemp, 2017). Furthermore, Spear- Swerling and Brucker (2003, 2004) presented evidence of a correlation between teacher knowledge about language (namely, structure knowledge) and student outcomes.

It is therefore imperative that schools support all teachers to build their knowledge and confidence in the teaching of language and linguistics, not simply provide programmes which have no relevance to the needs of the students in their room.

Mrs Katharyn Cullen is the Assistant Head of Junior School at Seymour College in Adelaide where she leads the delivery of academic excellence and rigour across the curriculum. Katharyn is currently completing her PhD at Torrens University where she is studying the interrelationship of morphology, etymology and phonology on the teaching of English orthography.