The Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) experienced by Australian educators is significantly higher than other frontline workers such as paramedics, mental health nurses and psychologists, a new study has found.

The groundbreaking breaking research led by Dr Adam Fraser and Dr John Molineux from Deakin University is the final report from a preliminary nationwide study published in 2024 involving 2,285 educators, and which collected 1,068 stories of trauma and 107 detailed interviews.

The latest research reveals that STS is a significant threat to teacher wellbeing, mental health and retention, with 37.3% of those surveyed saying they’re likely or extremely likely to leave the profession due to STS, and a further 18% unsure if they will remain.

Despite this, many educators reported receiving no formal support or training to manage STS – unlike their counterparts in health and emergency services.

‘Educators aren’t entering the profession prepared for this’

Dr Adam Fraser, the report’s lead researcher, said while he and his team have been studying how to reduce burnout as a way to address Australia’s teacher shortage, the profound impact of STS is a significant contributor that isn’t being talked about.

“Educators aren't entering the profession prepared for this. Unlike social workers or psychologists, they don't expect trauma as part of the job – and we haven’t put the support structures in place. Their training doesn't prepare them, and we’re not mitigating the impact,” Dr Fraser told The Educator.

“The education system lags behind sectors like health, social work, and emergency services in training, support, and even basic supervision. Other professionals get time out after traumatic incidents, but teachers are told to just push through.”

Suffering in silence

Dr Fraser said what’s surprising is how bad this issue has become without it being a major talking point in policy discussions.

“We hear more about direct trauma – violence, for example – because it’s visible and immediate. But secondary trauma is a lot harder to see. So, we want this study to shine a light on how deep the issue runs, and how educators are suffering in silence,” he said.

“Unfortunately, it’s been hard to even start the conversation. Many schools told us, ‘You deal with it.’ Educators were basically left to find their own support strategies.”

The study found 16% of educators said they are significantly depressed and 50% said they experience some degree of depression due to the silent struggle they deal with. Burnout also remains widespread, with 70.8% of educators scoring in the moderate to high range, and 61.4% frequently reporting feelings of overwhelm.

“This is not burnout alone. This is deeper. It’s the cost of witnessing the impact of student trauma, day after day, with no buffer, no outlet, and no support,” Dr Fraser said.

A positive finding from the study was how resilient some educators were in the face of the profound pressures they deal with daily, Dr Fraser said.

“What stood out to us were the ‘diamonds’ – those who are created under great pressure but still manage to sparkle brightly.”

‘Every day is totally unpredictable’

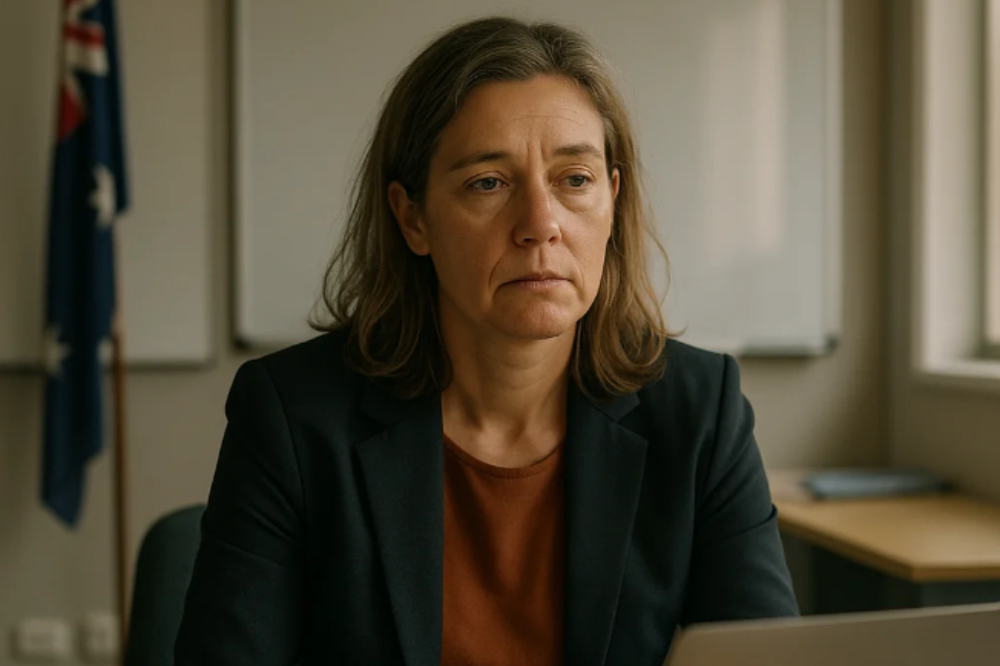

One primary school principal who contributed to the report said every day at her school is “totally unpredictable”, with staff regularly providing post-weekend trauma support.

“The kids are coming to school completely not ready to learn because there’s often been a lot of problems at home during the weekend,” the principal told The Educator.

“Staff are constantly trying to help kids feel safe through ongoing support and liaising with allied health providers, but these services are often short on the ground so they’re triaging things. One of the most frustrating things is not knowing what to do with some children who are in traumatising situations.”

The principal said she had learned to deal with the pressure of the job over time by maintaining a strong collegial support network and remembering that she isn’t alone.

“Dealing with STS is not something you’re ever taught how to do, so having that collegial support, calling a colleague who understands – whether that be a staff member or your principals’ association – is important,” she said. “At the very least, it helps you know that you’ve done things the right way.”

The principal said any principal dealing with STS should be mindful of having those structures in place for when times get tough, which sadly, is most of the time.

“It’s so important to check in with staff at end of day for mutual support, and remember that there is help from system supports – even if they are limited – but always remember that the greatest support is your staff who are right there with you and sharing the burden.”

What can be done?

The report made a series of recommendations for systems and policymakers to consider.

- Formal recognition of STS as a professional risk for educators

- Introduction of STS as an area in all undergraduate teaching degrees

- Provision of highly effective evidence-based self-care training to mitigate STS and Burnout

- Provision of trauma-informed practice training at a school level for better student outcomes

- Access to professional supervision for educators

- Increased funding and resourcing to child and health care services and systems – mental health care services, department of child services to meet the levels of mandatory reporting

- Better coordination between schools and community services in regions

- Timely and effective responses from mandatory reporting systems

- Supervisor support for School Principals as they provide supervisor support to their teachers

Dr Fraser said the reason some initiatives targeted at reducing the overwhelm that teachers and leaders feel haven’t worked is that they don’t address the real causes.

“Highly effective self-care training is the only intervention that affects all three: compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout,” Dr Fraser said. “But it has to be paired with things like supervisory support – especially for principals, who are holding everything together.”