In December, Federal, state and territory education ministers approved The National Teacher Workforce Action Plan, paving the way for significant improvements to teacher supply, initial teacher education and respect for the profession.

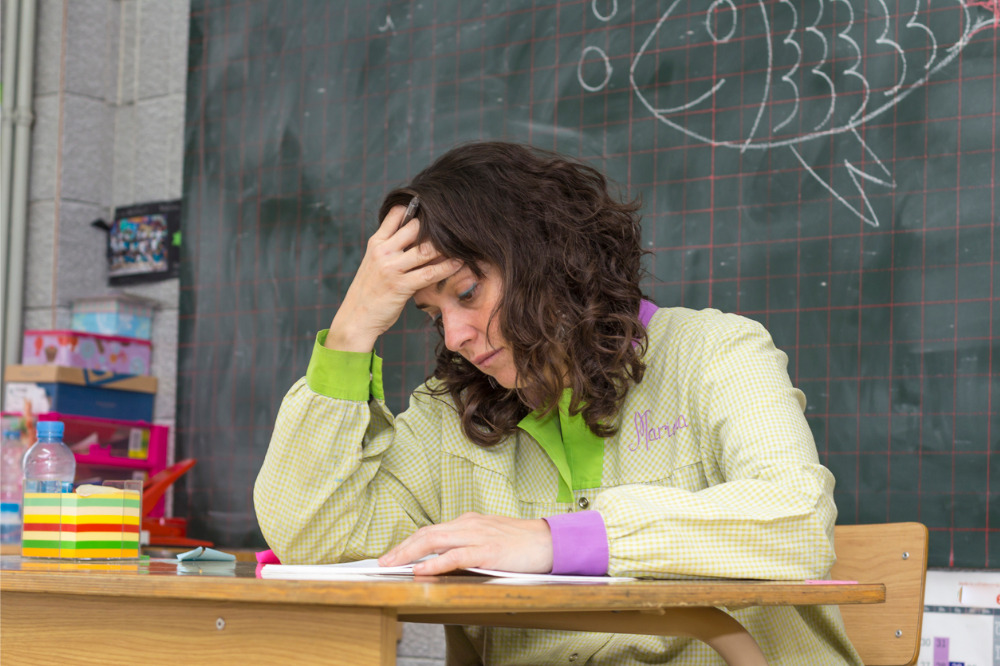

Importantly, the plan also includes a commitment to independently evaluate State and Territory Government initiatives to reduce teachers’ workloads amid reports that a staggering 84% of educators are thinking about quitting the profession altogether.

A 2022 Productivity Commission report found the majority of teachers cited heavy workloads and poor work-life balance as the main reasons why they’re thinking about leaving the profession. A key finding in the report was that much of this workload involves “low-value tasks” like paperwork and other clerical duties.

A tragic cause and effect cycle

Education experts like Scientia Associate Professor Rebecca Collie from the University of NSW School of Education warn that as long as teachers feel overwhelmed and burnt out, they’ll continue to leave the profession in droves.

“Teacher and principal burnout and attrition are significant and growing concerns in Australian schools, and a key factor implicated in these concerns is teachers’ working conditions,” Scientia Associate Professor Collie told The Educator.

“Poor working conditions are linked with lower wellbeing and retention, whereas helpful working conditions are linked with many positive outcomes for teachers, students, and schools.”

Associate Professor Collie said efforts that not only reduce poor working conditions, but also improve helpful working conditions in schools are essential for addressing the school workforce crisis.

“Poor working conditions commonly experienced by Australian teachers include high workloads and disruptive student behaviour,” she said.

“To reduce teachers and principals’ workloads, it is important that efforts focus on streamlining administrative work so there is more time for the core business of teaching and learning.”

What schools can do

Associate Professor Collie said schools may also want to experiment with different ways to reduce teachers’ workloads, such as through meeting free weeks or collaborative approaches to planning.

“To help teachers and school leaders be better equipped to navigate disruptive student behaviour, effective and evidence-based professional learning opportunities can be helpful – particularly those that align well with teachers’ goals for improving their classroom management skills,” she said.

“At the same time, it is also important that efforts are made to support students’ wellbeing, mental health, and behavioural needs, as these often feed into disruptive behaviour in the classroom.”

In contrast to those poor working conditions, there are some helpful working conditions that encourage teachers to remain in the profession, Associate Professor Collie said.

“These include giving teachers opportunities for input in decision-making, prioritising positive interpersonal relationships in schools, and providing effective professional learning and mentoring for all teachers.”

“Unless efforts are made to improve current teachers’ working conditions, it is likely that any new policies to attract teachers to the profession will be hampered by a ‘revolving door’ of staff turnover.”

‘Difficult conversations are needed’

Dr Fiona Longmuir, an educational leadership lecturer at Monash University's School of Education, agrees that teacher burnout has exacerbated school workforce shortages, but said negative public discourse from politicians and the media, as well as the lingering effects of the Covid pandemic, have also contributed to the problem in a big way.

In 2022, Dr Longmuir and other researchers from Monash conducted The Australian Teachers' Perceptions of their Work Report 2022, a comprehensive national survey of more than 5,000 teachers nationwide.

“We asked teachers to share their ideas for what needs to change in order for them to feel more supported in their work,” Dr Longmuir told The Educator.

“Their suggestions indicated that there are several broad, political and systemic challenges that need attention, but also there are some things that can be done at a school and community level to show greater support to our teachers and enable them to do their important work in the best way possible.”

Dr Longmuir said “difficult conversations and decisions about what we want schools to be and do” are needed if meaningful change is to be seen.

“One immediate actions that could have impact includes changing the way students, parents and community members talk about and with teachers with a goal of increasing respect, trust, and support,” she said.

“Another is looking at immediate ways to address workload conditions, which may involve assessing and prioritising the myriad of teachers’ duties and letting some things go.”

Flexible options for staff can make a difference

Dr Longmuir said schools and education policymakers should also think about how they might attract teachers back into classrooms.

“For example, those who have dropped back to part time, recently retired teachers, and those on family leave. With flexibility and an openness to new ways of working, they might be able to find a way to return to a classroom,” she said.

“A simple example might be greater flexibility for part-time work. At the moment, flexible, part-time arrangements are often the exception to the rule, rather than an accepted and easy to access choice.”

Dr Longmuir concludes: “The most important way to make a difference to the health and wellbeing of our educators in Australia is to listen to teachers, respect the important work that they do, and be open to new ideas and approaches that will support them.”