A widespread loss of leadership in Australian schools over the next 12 months is the new number one threat to the nation’s education system, the 2023 State of the Sector report by PeopleBench has warned.

The survey, conducted between March-May this year, gathered the perspectives of nearly 500 school staff, including principals, senior leaders, middle leaders, teachers, and HR/support staff about the challenges and opportunities they face in the school workforce.

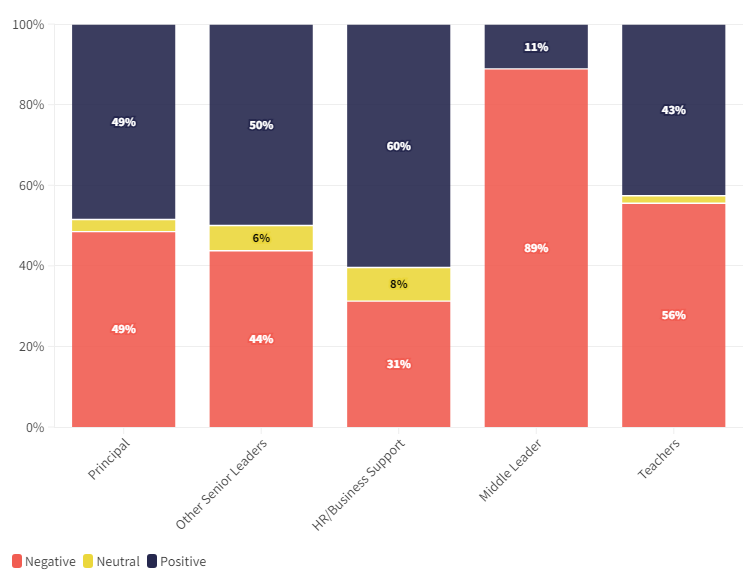

It found that teachers and middle leaders are the least likely to report feeling positive about their work, the culture of their workplace, and the alignment between their values and the values of their school.

However, these staff are also least likely to intend to stay in their role for the next 12 months, widening the scope of an already crippling teacher shortage.

The study’s findings highlight a potent tale of two different experiences of work within the sector: that of school leaders and classroom teachers.

The difference between the two cohorts was stark, with principals and senior leadership colleagues expressing more optimism about their roles and the future of their schools compared to teachers and middle leaders.

2023 State of the Sector report

“As middle leaders constitute a significant portion of potential future senior leaders and principals, this raises serious concerns about the sustainability of the leadership pipeline,” PeopleBench Chief Research & Insights Officer, Mike Hennessy said.

Casual, relief, and short-term contract teachers are also leaving the job in greater numbers, the report found.

“With so many teachers leaving the profession – and a dwindling supply of new teachers coming through universities – schools are scrambling to fill gaps in their teaching workforce, and this has created high demand for short-term teachers,” Hennessy said.

“Other ongoing issues also continue to compound these supply shortfalls, as survey respondents frequently cited high workloads and work intensification as major challenges. These issues have placed the wellbeing of staff – and therefore the retention of those staff in schools – at risk.”

‘The current model of schooling is unsustainable’

Dr Renae Acton, Research Program Manager at PeopleBench, said the global teacher crisis stems from an unsustainable schooling model, not a lack of passion or commitment from educators.

“The model of schooling as we have it now is unsustainable and the future of the school workforce has to look different. The sector can't continue to deliver schooling under the same conditions, using the same paradigm, because we simply won’t have enough teachers,” Dr Acton said.

“What I’d love to see is more flexibility built into the system – more flexible models of delivery that respond to student needs, more flexible professional learning that supports staff’s career aspirations, and more flexible job design where educators can craft a role that reflects their professional strengths and interests.”

‘Protective factors are weakening’

A damning survey of 2,500 principals earlier this year found the number of Australian principals planning to quit or retire has tripled over the last four years with teacher shortages a main driver of the profession’s stress.

Dr Paul Kidson, Senior Lecturer of Educational Leadership at the Australian Catholic University, said the cumulative impact the ACU’s data suggests the rate of school leaders walking away from the job might be speeding up.

“Each year, we typically see two or three of the 19 stressors average rate a seven out of 10 or higher; this year we reported that seven stressors are now averaging over seven,” Dr Kidson told The Educator.

“In other words, much more is being demanded of principals, and nothing is being taken away from their work. The combination of the top five stressors has never occurred in the previous eleven surveys.”

Sheer volume of work – which leaders report as the biggest stressor – and not enough time to focus on teaching and learning – the second biggest stressor – have been consistent since 2011, he said.

“Teacher shortages are now ranked as the third biggest stressor, up from twelfth last year. On top of that, supporting the mental health and wellbeing of students [#4] and teachers [#5] means the stress of school leaders’ work is escalating,” he said.

“What concerns us greatly in this year’s data is that protective factors are starting to weaken.”

Middle leaders becoming increasingly vital to schools

While there is no shared definition of middle leadership in Australia, the impact these staff have on teaching and learning is profound, says Mark Grant, CEO of the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

“Across many of our 9,600 schools, middle leaders are vital when it comes to maintaining and driving improved school performance, often holding specialised leadership roles that draw on their teaching experience and expertise,” Grant told The Educator.

“When middle leaders share their knowledge, it benefits not only their colleagues but students as well. Covering pedagogical, program or student-based leadership, middle leaders are pivotal to a school’s success – the backbone of expertise and support for classroom teachers, working collaboratively to create high-impact learning opportunities for students every day.”

A report by Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), titled: ‘Middle leader educators – who are they and what do they do?’ finds that middle leaders are highly experienced educators, often promoted to their role because of their high-quality teaching skills and experience.

Grant says that a shared definition of the Middle Leader role would have many important benefits for school communities.

“We know that middle leadership is an important role, both for teaching staff and for a school’s senior leaders. Having a shared definition will mean our middle leaders will have their own framework that clearly defines relevant professional knowledge and practice, no matter what role they play within their school,” Grant said.

“It also means their progression pathways will be more clearly defined, with a shared understanding of where to focus their professional growth and development opportunities – enabling them to maximise their impact and potentially move toward more senior leadership roles.”

Better times lie ahead

Despite many gloomy findings from the report, Hennessy said he remains hopeful.

“For the first time, the 2023 State of the Sector report asked direct questions about what is going right in schools, as the positives are not spoken about nearly enough,” Hennessy said.

“In spite of the many challenges, schools remain places where incredible work is done: meaningful work that can create a true sense of purpose for those who perform it, and with massive potential for positive social impact.”

Hennessy said many of the potential solutions to Australia’s education workforce challenges already exist in other industries, ready to be adapted to the education context.

“Plus, there is immense wisdom already in the sector – staff know what needs to change, we just need to ask them, take their input seriously and act on it,” he said.

“Our data tells us that educators want to be involved in the big decisions that affect how their school operates. Engaging them in this kind of conversation to recreate the teaching jobs of the future is where we need to start.”